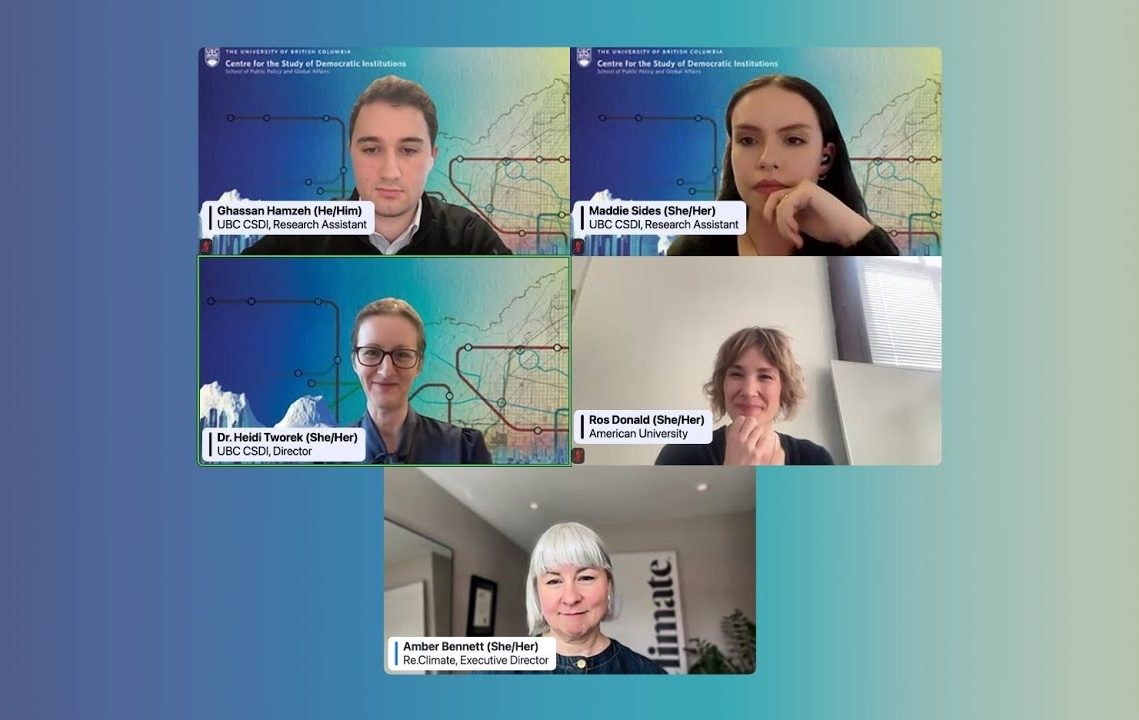

Authors: Netheena Mathews, Joel Sawyer

Co-authors: Heidi Tworek, Chris Tenove

Photo credit: Othmane Khaled

What happens when GenAI (generative artificial intelligence) disrupts an election? What roles do different stakeholders like election management bodies (EMBs), civil society, journalists, academics, and tech companies play in protecting election integrity? What new informational risks does GenAI introduce and how might malicious actors exploit them? These were some of the urgent questions raised in tabletop exercises led by UBC’s Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions (CSDI) at the Technology and the Future of Democracy conference, held in Vancouver on September 10, 2025.

Modelled on election exercises published by Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center and simulation exercises used in emergency and pandemic preparedness, the tabletop exercises were designed to prompt reflection on roles, strategies, and information gaps related to technology-facilitated election threats. The two sessions, led by CSDI’s Heidi Tworek and Chris Tenove, generated helpful insights from the academic and practitioner participants.

How it played out

The exercise was situated in the fictional country of Cascadia. This was Cascadia’s first national election in which the electoral management body could compel platforms and internet sites to take down election-related disinformation and violent incitement. Participants received more contextual information on Cascadia to make the exercise more focused and concrete.

Participants were divided into sector-specific groups: government, civil society, academia, technology companies, and nefarious influencers. Each group was given a list of specific actors to represent the different opinions and agendas within the sector. That ensured, for example, that civil society was not treated as a homogeneous bloc, but included perspectives ranging from civil liberties advocates to journalists to groups advocating for religious and ethnic minorities. Groups contained actors ranging from election management officials deciding whether to compel content takedowns, to tech companies with diverging views on free speech, to a teen influencer willing to amplify disinformation for profit.

The exercise unfolded in four phases:

- In the baseline scenario, participants considered their sector’s role in protecting election integrity, and the threats posed by AI.

- With ‘Inject 1’, a complication was introduced: deepfakes that disparaged candidates, including sexualized images, had surfaced online but thus far received few views. In this phase, the different sectors assessed the threat level posed by the scenario, debated whether Elections Cascadia should compel takedowns, and outlined sector-specific responses.

- With ‘Inject 2’, participants addressed a late-campaign crisis when a fringe, anti-government streamer called for followers to prompt AI models to create content for a campaign alleging that ballot-counting machines were defective.

- Sessions ended with reflections on lessons learned and broader themes to consider.

To capture how participants’ perceptions shifted before and after the simulation, CSDI ran pre- and post-exercise surveys using Mentimeter. These surveys asked attendees to rank their perception of the severity of AI threats to election integrity, the need for takedown action on social media by EMBs, and the contributions of researchers and academics in addressing informational threats. Combined with the simulation exercise, the surveys illuminated how participants’ views evolved once they had grappled with the cascading complexities of AI-enabled disinformation under the tight time constraints of a tabletop exercise.

Learnings & reflections

Photo credit: Othmane Khaled

The surveys of 14 participants in session 1 and 13 in session 2 showed that AI threats were perceived as growing risks to election integrity. Aggregate results from both groups found they rated this risk at 3.9 on a 5-point scale in the pre-session survey, which increased marginally to a 4.0 average when surveyed after the sessions. There was significant support for the statement that academic researchers play a major role in addressing informational threats, which rose from 3.6 to 3.8 between pre- and post-session surveys. Participants across both groups also agreed that EMBs should have the authority to order content take-downs (rising from 4.3 to 4.4).

However, there were variations between the two groups. In one group, concern about AI-enabled risks was higher (rising from 4.5 to 4.6), as was the perceived role of academics (from 4.3 to 4.6) and endorsement of takedown authority for EMBs (rising from 3.8 to 4.1). The other session’s participants started with lower levels of concern that remained largely unchanged after the exercise. The second group perceived AI as a moderate risk (3.5 before and after), showed a small rise in support for takedown powers (from 3.4 to 3.5), but a slight decline in agreement on the role of academics (from 4.3 to 4.2). These differences between participant groups, and the impact of tabletop exercises on them, warrant further investigation.

Participants across both groups rated ‘Inject 2’ a bigger threat than ‘Inject 1’, particularly given its timing on the eve of voting and its impact on public trust in election processes. This underlines how responses to technology-based election threats must be tailored to address specific risks at specific times and cannot follow a one-size-fits-all approach.

Participants discussed how even ‘low-risk’ scenarios could quickly spiral out of control in a polluted information landscape. Besides outlining the direct impacts of technology-facilitated disinformation, the participants considered ‘second-order’ risks posed by regulatory interventions such as content takedowns by EMBs. These nuanced discussions highlighted how interventions themselves may carry risks. The discussions also delved into how ethical responsibility and strategic reasoning do not end at publicizing or uncovering wrongdoing or reporting it, but also require thinking through the actions that would ensue.

As groups considered the “known unknowns” in scenarios, including who was behind content, how far it might spread, and what audiences it could affect, they confronted the challenge of coordinating a unified response among diverse actors, particularly under time constraints with limited information.

The scenarios also illuminated the trade-offs facing each sector. While one civil society group grappled with whether to demand Elections Cascadia’s action on deepfakes that might not meet legal thresholds, another group of academics debated whether publicly exposing harmful content might amplify its impact.

Participants noted a greater appreciation that sectors are not monolithic. This recognition is important while considering the political and strategic realities in each sector. For instance, the group representing tech companies had diverging approaches to protecting and promoting free speech, and saw their responses as branding opportunities as well as exercises of civic duty.

Conclusion

While the tabletop exercises were not meant to produce a prescriptive playbook for securing elections, they prompted participants to think more deeply about how AI-enabled operations might unfold in upcoming elections, and what that means for safeguarding election integrity. Overall, discussions from both exercises highlighted how all sectors could play a role in addressing or exacerbating potential issues connected to GenAI.